Save a life, save the world

let's rescue humanity together,

support our missions in the Mediterranean

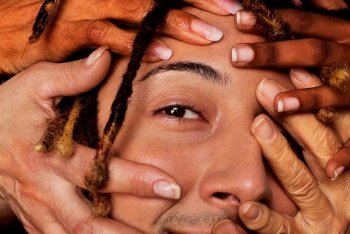

As the country's right-wing government takes a hard line on immigration in the Mediterranean, hip-hop artist Ghali becomes a leading voice for solidarity.

In mid-March, a few weeks after a shipwreck off the Calabrian coast, the waters of the Mediterranean were still carrying the remains ashore: wooden planks, engine parts, children's shoes, corpses. Shipwreck season was early this year for migrants.

Four hundred kilometres away, in the Sicilian waters off Trapani, in preparation for future crossings and tragedies - which happen all the time, but are treated by rich countries as if they were a new crisis each time - volunteers from all over Italy and abroad spent the weekend learning how to carry out rescue operations at sea. The training sessions were attended by inexperienced people and veterans, people who in normal life are teachers, paramedics, students, seafarers; there was even a chef.

On Sunday, they were joined by a special guest; he could have blended in, dressed like the others in a blue helmet and windbreaker, had it not been for the stares, some even squinting in surprise - the price of being so famous in his native Italy, where he is now known by name in every home: Ghali, which means "precious" in Arabic.

The previous summer, rapper Ghali had donated a RHIB (Rigid-Hull Inflatable Boat) to Mediterranea Saving Humans, the non-profit organisation that organised the training, a type of orange rubber dinghy that can be quickly armed to reach people in danger at sea and bring them to safety on the mother ship. Ghali, who was born in Milan to Tunisian parents, has repeatedly described the purchase of the dinghy as "the most rap-thing he can do". He often adds: "And it's not enough.

He named it after a song from his latest album, 'Bayna', which means 'It is clear' in Arabic. Although the Bayna was due to set sail at the end of September last year, it has yet to make a single voyage, hostage to the internal struggles of Italian politics. Since last October, the country has been led by Giorgia Meloni, the leader of the far-right Fratelli d'Italia party (which was taken over by Mussolini's followers after his death). Before becoming prime minister, she had said that NGO rescue ships, which she called 'ferries' and likened to human traffickers, should be sunk. Her government has actively sought to minimise the time spent at sea by the 20 or so search and rescue vessels that patrol the Mediterranean. Mediterranea's ship, the Mare Jonio, is the only one flying the Italian flag, which makes it subject to the control of the Italian authorities.

The tragedy off the coast of Calabria - 94 bodies have been recovered and 11 more are presumed dead - has reignited debate about the country's approach to migrant sea crossings. Ghali's trip to Trapani to launch Bayna was planned in the hope that the publicity would help raise awareness and unblock the Mare Jonio's certification, allowing it to return to the water by spring, when crossings are expected to resume in large numbers.

After strapping on his life jacket, Ghali climbed into one of Mediterranea's two old orange rhibs, struggling with his six-foot-two frame to take his seat. The volunteers split into two teams, with one boat assigned to the migrants and the other to the rescuers. Ghali was on the boat of those to be rescued. The other boat quickly moved away.

The exercise they were doing - approach and first contact - can be extremely dangerous. It requires the rescuers to establish a relationship of trust with those on the other boat as quickly as possible, and to express authority in a firm but non-threatening manner. After days at sea, often drifting, migrants may rush to disembark from their (often fragile) boat, risking capsizing.

Ghali's rhib volunteers, who had been practising all weekend, spotted the approaching lifeboat. At the signal, they stirred and shouted in English: "Hello! Hello! We are here!" A friendly "Hello!" came back from the lifeboat. "We are an Italian ship, we are here to help you all," explained a volunteer named Gabriele Mantici, a professional skipper and free diver. "But you have to stay calm."

A chorus of "Come, come" is the response from Ghali's boat, which has begun to sway noticeably.

"Sit down," Mantici says in a calm tone. "We are here to rescue you. We will take you to that ship over there," he says, pointing to the Mare Jonio. "But you must remain calm and sit down."

"Please, please," they replied, and Ghali, who had understood the script, suddenly stood up and waved his arms. The rhib swayed again.

Fabio Gianfrancesco, deputy rescue coordinator of Mediterranea, who in life is a philosophy professor in Rome, takes a moment to explain things to Ghali. "His position is important," he says, pointing to Mantici. "The speaker is the highest, he stands with one foot on the edge. This makes sure that those about to be rescued focus on that person."

"OK, I'll hand you a life jacket," Mantici says. "You put the vest on and close it with the belt," he continued, mimicking the procedure, doing by slipping the vest on and closing the belt. "When you all have your lifejackets on, we bring you on board one by one. But you must remain calm."

Gianfrancesco bent down and added in a low voice: "Communication through gestures is the only way to be sure of getting the message across."

The 'migrants' rushed to grab their life jackets and the rhib, even in the harbour water, jerked.

Go back, go back,' Mantici says to his crew, and their rhib is pulled back. To Ghali's group he says: 'If you do that, we can't help you. OK? You need to stay calm and listen to me. OK?"

The Ghali rhib calms down and the RHIB gets close enough to hand out the lifejackets. Once everyone is strapped in, the transfer begins.

Back on board the Mare Jonio after the exercise, Ghali sees that Bayna has finally been inflated. The idea of donating her was born over a year ago. Now, finally in her presence, he caresses her and exclaims: "What a bomb!"

Few people come to the top deck to see Ghali write 'Bayna' on the hull. People have to get back to their daily lives, there are flights to catch. But those who were there applauded. Ghali himself seemed lost in thought.

Asked who he thought was being rescued, he replies: These volunteers are saving my friends, their families, my brothers. I feel gratitude. My brothers are saving my other brothers. He continued: 'They save me.

In the chorus of one of Ghali's biggest hits, 'Dear Italy', he sings: "When they tell me, 'Go back home,' I say, 'I'm already here. Italy".

It is not only xenophobic Italians who fail to understand that for someone like Ghali, Italy is home. Even fans who profess their love for the singer still ask him: "But when did you come to Italy?" The persistent perception of Ghali as a foreigner stems in part from the way Italy sees itself: as a country with a grandiose history of emigration - the Italian diaspora has settled in America, Europe and Australia - but not of immigration.

Ghali has challenged Italy's self-image by recounting his own experiences as the son of Tunisian immigrants in songs so popular they have even been used in adverts for BMW, McDonald's and Oreo; 'Cara Italia' is ubiquitous in a well-known Vodafone ad campaign.

Although Ghali was born in Italy, he did not become a citizen until he was 18, after what he describes as a complicated bureaucratic process caused by Italy's decades-old citizenship law, which is designed to keep the diaspora's ties with Italy strong, not to integrate newcomers. Italy recognises descent as a requirement for citizenship, even if a citizen's family has not lived in Italy for generations. But unlike the US, for example, there is no automatic grant of citizenship to those born in Italy to non-Italian parents. This is the difference between ius sanguinis and ius soli: belonging by blood versus belonging by soil (of birth).

In the song 'Flashback', Ghali sings: 'Interviewers ask me: 'Ius soli? I just think we are more alone', a play on words between the Latin soli (of the soil) and the Italian 'solo'.

Those born in Italy to foreign parents are referred to as second-generation immigrants. (Children born in the US to immigrant parents are considered 'first-generation' Americans). The broader definition also includes people who arrived in Italy before the age of 18, as well as those who, like Ghali, have acquired Italian citizenship. In 2018, there were around 1.3 million second-generation minors in Italy in the broad sense, three-quarters of whom were born in Italy. They represent 13 per cent of the Italian under-18 population.

Ghali's mother left Tunisia when she was 20. Ghali says his father arrived years later and, after becoming a drug dealer, was in and out of prison and Ghali's life until he left for good and returned to Tunisia. With his father's second arrest and the end of what Ghali calls the haram flus - illegal money - his mother found work as a janitor, cleaning houses and hospitals. It was Ghali and his mother against the world, or, as he sings in 'Flashback', together in 'guerrilla warfare'.

It was she who took him to see the American film '8 Mile', starring rapper Eminem, in 2003. He was immediately taken by this "American thing", rap. An older Tunisian boy soon introduced Ghali to the work of Joe Cassano, a young rapper who died in 1999, and gave Ghali a CD of Italian rap. He devoured it. Discovering that rap could be done in Italian, a language he loved, was a revelation.

Ghali arrived on the Italian rap scene at a time when, like Eminem, emerging Italian rappers were transforming the genre to narrate their personal conflicts, often as outsiders in society. Andrea Bertolucci, a journalist who covers Italian rap, contrasts this approach with the period in the 1980s and 1990s when rap in Italy was adopted by militants of left-wing movements, with lyrics expressing more complex political ideas. Cassano, says Bertolucci, was "a true lyricist and pioneer" in that he spoke about himself with great introspection. But in both phases, he says, "rap was not censored because the big record companies paid no attention to it; it was a subversive genre, a free genre".

And Ghali, who spent his childhood summers in Tunisia, then under the control of a repressive regime that had been in power since 1987 (Ben Ali, ed.), experienced this freedom first hand. He was reminded, as he listened to American and Italian rappers fearlessly denouncing the police, that in Tunisia the same act could lead to imprisonment.

The year Ghali discovered rap, he and his mother moved into a council house in Baggio, on the outskirts of Milan. Rap became a way to connect with his peers; even today, his private circle is largely made up of people from Baggio. "Even before he became famous, Ghali was famous for us," says his friend Nathan Bonaiuti, whose mother immigrated from Eritrea.

Soon Ghali was recording tracks in his room, quietly so his mother wouldn't hear the swear words, and distributing the recorded CDs around Baggiodemo. "Rap made sense of everything," he says. "Nobody can stop me saying what I think."

But the freedom he found in rap contrasted with his reality. Ghali says he always felt Italian: "In kindergarten with the nuns, I used to recite the Ave Maria!" But his identity card was markedly different from a normal Italian one, an effective reminder that he was a "guest".

This rejection was reinforced by the media. "There was never a news report that said 'Tunisian' as a positive thing," he says. "Only 'A Tunisian was raped'. A Tunisian was arrested'. The Isis members were three boys of Tunisian origin'. I was even ashamed of my name'".

As a teenager, Ghali became a hype man on stage for some of Italy's biggest rappers. "It was a badge of honour to be an Arab," he says. Eventually, he took to the stage solo, sure he could make it. "I was telling a story that had never been told, and I knew there were other people like me," he says. "I was in love with Italian rap, but I didn't feel represented; they weren't talking about me specifically. And I knew that the children of immigrants were starting to exist in Italy, but no one was telling their story.

And so he told his story, using the mix of languages that is his everyday slang. In Ghali's texts, the subject, verb, object and adjectives of a single sentence can all be in different languages. They use irony rather than aggression. Of course he was angry about a lot of things, but, he says: "If I'd said certain things, I wouldn't have had a chance. I was already at a disadvantage because I was Arab; I had to be liked. I did not just want to be accepted by the 'street kids'; I wanted to be accepted by Italian families. I wanted to be recognised as a national artist.

The glorification of his mother has probably helped him win over many Italian mothers, a demographic perhaps unexpected for a rapper (in 'WilyWily' he describes himself as 'mama's son and his sacrifices').

In 2018, the sold-out show at the Mediolanum Forum in Assago is broadcast live. The camera pans over the crowd, singing along as Ghali switches between languages. The crowd goes into ecstasy when his mother comes on stage carrying an Italian flag.

However, his love for Italy has sometimes made Italians deaf to the criticism he expresses. Many Italians seem to interpret the song 'Cara Italia', whose official video has been viewed more than 100 million times on YouTube (the Italian population is around 60 million), as a true love letter, when in fact the lyrics are critical:

What kind of politics is this? What is the difference between left and right? They change the ministers but not the soupThe toilet is here on the left, the bathroom is down on the rightStraight down my streetBetter than nothing, más que nadaVabbè, tu aspetta sotto casaIf mum doesn't like you, I don't like youShe tells me "I knew it" but I don't believe itI'm not stupidSome people are closed-minded and have stayed behind, like in the Middle AgesThe newspaper abuses it, talks about foreigners as if they were aliensWithout passports, looking for dinero

As Italy debates whether to embrace its burgeoning multiculturalism or find a way to erase it, the second generation is largely excluded from the political debate. But with his music, says Bertolucci, Ghali has "finally given a voice to a community that has never had political, social, religious or even linguistic representation".

Bertolucci points out that Ghali's innovative mixing - or even 'contamination' - of the Italian language with Arabic, French, Spanish and English, as well as his use of cultural references common to many second-generation young people, 'created a linguistic claim for those who, like him, felt excluded from the right to citizenship and integration'.

But with its references to universal emotions and the youth of the 1990s and 00s - the two Justin Timberlakes and Bieber, Pixar and Pokémon - Ghali's music is also what Bertolucci calls "an engine of cultural access" for all Italians.

As Ghali sings in 'Bayna': 'You dream of America, I dream of Italy. The new Italy'.

In Ghali's life and music, the Mediterranean is ever-present, an acknowledgement of what binds and separates the destinies of those who live on its shores.

During the many summers he spent visiting his family in Tunis, Ghali was always aware of the siren call of the Mediterranean. Many Tunisians leave Tunisia in search of a better life, but for those who cannot obtain a legal visa to seek opportunities elsewhere, there is always the sea crossing, an option that is both expensive and dangerous.

Ghali would often hear adults in the living room crying because someone - a friend or relative - had drowned trying to reach Italy. It was something that was always, always, every year," he says.

In Tunisia and other North African countries, those who make the journey are known as harraga, or 'burners', because when they reach the other side they set fire to their identity documents so that the European authorities will not know who they are or where to deport them.

There is a whole body of music about the harga, the crossing. The songs revolve around recurring themes: the desire to leave, the dangers of the crossing, the suffering of exile and of the family left behind, the acceptance of divine will. To calm their nerves when the seas are rough, migrants on the boats sometimes sing these songs together. Ghali ended up writing one himself.

During a summer holiday when he was 16, Ghali arrived from Italy and began to describe life in Milan to his Tunisian cousin. Soon after, the cousin, who was only a few years older than Ghali, disappeared. The family spent hours looking for him. He finally returned late at night, covered in engine grease. He had been caught trying to hide on a boat bound for Italy.

For years, Ghali felt guilty that his teenage bravado could have cost his cousin his life. He wrote the lyrics to the song 'Mama' based on this experience.

In the video, a young Tunisian man wearing an Italian national football team shirt plans to leave in the middle of the night. Ghali sings:

He looks at me, my Nike Airs and thinks it's easy to be cash but he doesn't know it's notEnds up like the others doing weshwesh, bang bang, he knows.

But Ghali knows that this won't convince him, because he knows that if he had been born in Tunisia, he would have made the same decision to leave. Instead, he turns to the sea:

Sea or sea, don't worry, I advise, bring him to safetyAhi ahiahi, sea or sea, please don't worry or I'll drown.

I recommend he comes, bring him safely to shore.

If Ghali was acutely aware of crossings and drownings, Italians generally were not, let alone Europeans from countries far from the Mediterranean.

But then crossings, which include refugees seeking asylum from war and persecution as well as economic migrants, more than tripled in 2014, partly due to the Arab Spring.

The explosion in migratory flows took Europe by surprise, as if it had forgotten that many of these countries lie just across the Mediterranean.

In the end, the sea was destined to become both an object of political contention and a graveyard. Since 2014, more than 27,000 people have died or gone missing trying to cross it, largely because Europe saw the Mediterranean as a border to be enforced rather than a search and rescue zone to be actively patrolled, a void that ships like the Mare Jonio seek to fill.

To prevent arrivals, the EU has focused on stopping departures from the countries of departure, essentially turning off the tap while the pipeline remains there.

To do this, it has effectively outsourced border control to countries on the other side of the Mediterranean that have much lower human rights standards than Europe.

The EU inaugurated this approach after the 2015 migrant crisis, when nearly one million people - some 80 per cent of them fleeing Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq - arrived in Europe by sea.

Most had left from Turkey, but after a 2016 six-billion-euro deal with the EU, Turkey is preventing people from leaving its shores in large numbers. (The agreement has also simultaneously strengthened - domestically and internationally - Turkey's increasingly authoritarian leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.)

The following year, Italy signed an EU-sponsored agreement with Libya, its former colony, to reduce the number of crossings from there.

Human rights organisations continue to denounce the agreement, having documented detentions, murders, disappearances, torture, enslavement, sexual violence and other acts committed by Libyans against people trying to reach Italy.

While it was the centre-left Democratic Party that made the deal with Libya, the Italian politician most associated with anti-migrant sentiment is Matteo Salvini, the leader of the far-right League party.

In June 2018, Salvini, who loves the media and bombastic statements, became both deputy prime minister and interior minister. During his 14 months in office, he imposed a series of draconian measures to abolish the main forms of protection for migrants and facilitate their deportation, closing Italian ports to rescue ships.

He argued (as Meloni does today) that these ships were a 'pull factor' encouraging people to cross the sea, rather than a 'push factor' encouraging them to leave. He refused permission for more than one rescue ship to dock, blocking them at sea. Salvini is currently on trial for his actions in one such case, and among the prosecution witnesses is actor Richard Gere, who visited the migrants on board.

In July 2019, in a remix by British rapper Stormzy titled 'Vossi Bop', Ghali targets Salvini, portraying him as a 'fascist politician' who says that 'those who arrive in a dinghy cannot stay'.

Ghali imagines the scene of an AC Milan football match (both Ghali and Salvini are Milan fans) and raps about how Salvini's presence ruins the atmosphere.

"I'm an artist and politics is not necessarily my job," Ghali said in an interview published on the day of the track's release. "My music tells my story and rap, which started as a social complaint and has always been my bread and butter, is the best medium to satisfy the need I have to take a stand against those who exploit fear to create an enemy."

Salvini, perhaps the most powerful man in Italy at the time, took to Twitter to argue with the rapper. Linking to a VICE Italia article with the headline "Ghali attacking Salvini in a song with Stormzy is pure joy", he quotes Ghali's lyrics before adding: "He insults me but I don't mind his music, is it serious?" with the sunglasses emoji.

The following month, Salvini overplayed his hand by trying to become prime minister. Instead, the coalition changes and the new government cancels Salvini's decrees.

A pandemic is on the horizon, and when the world comes to a standstill and travel slows down, so do migrant crossings. Italy, especially in the north, continues to be hit hard by Covid.

Salvini is railing against the mask requirement and other restrictions. The mayor of Milan, Giuseppe Sala, soon recruits Ghali to write the words for the video that accompanies the city's post-closure campaign. "We wanted to give the city a face and a voice that could represent the new generation of Milanese, a symbol of an engaged intercultural society," says Sala. "Ghali found the words to speak to everyone.

On a Friday evening at the Bice restaurant, a Milanese institution frequented by professionals and middle-class families, a woman in a suit who looks to be in her sixties comes out as Ghali enters. She recognised him immediately. I thought you were in Morocco,' she exclaims in genuine surprise. His last Instagram post had been from Marrakech itself.

Ghali had not made a reservation and the restaurant was full. He seems willing to wait, but the enthusiastic waiter finds him a table in the corner.

Bice is in the fashion district, the heart of the Italian fashion world, and has fallen in love with Ghali. Whether or not the other diners knew who he was, they probably understood that he was famous. Whether they understood that he was Italian is another matter.

This quality of Ghali's - the feeling that he could come from many places - made him attractive to Italian fashion, says Federico Sarica, head of content at GQ Italia, which put Ghali on the cover of the magazine for the second time in May 2022.

Ghali immediately appealed to the fashion industry because he was the Italian artist who looked most like the rest of the world,' says Sarica. The reason for this gap to be filled is simple, Ghali argues: Italy is always far behind.

It was all made easier by the fact that Ghali is tall, handsome and dresses well.

United Colors of Benetton chose him as its brand ambassador for 2021 because he "embodies the company's core values of multiculturalism and integration" and called him "one of the most influential artists of his generation". Ghali will design a collection for Benetton in autumn 2021, including a men's hijab and clothing with Arabic lettering.

Ghali was absolutely new to Italy,' says Roberto Saviano, the journalist and essayist perhaps best known outside Italy as the author of 'Gomorra'.

For Saviano, Ghali is absolutely Italian: 'He's a milanista! - without ever hiding his Tunisian origins. This simple synthesis," he explains, "allows Ghali to both normalise the second generation and humanise those who go to sea.

Saviano quotes the song 'Mamma', saying that it 'tells the drama of leaving by sea better than any news story, book or film, because it tells how and why a boy decides to leave, and does not hide the contradictions'.

Karima Moual is an Italian journalist of Moroccan origin who writes about these contradictions - including the constant obstacles to integration and equal opportunities - for national newspapers such as La Stampa and La Repubblica, and as a columnist for Mediaset, the country's largest television network.

Despite these very Italian credentials, she says, "I will always remain 'the journalist of Moroccan origin'". For her, what is missing is "that step forward, the recognition that there is a generation, all Italian, with a migratory background but integrated, who do not want to 'go back' - who see their future here".

With regard to Ghali, he says: 'Finally, there is a second generation, a "foreigner" who crosses borders. He is no longer 'the Tunisian'. Ghali is Ghali'.

GQ's Sarica warns against turning Ghali into a symbol or thinking that Italy "looks more like Ghali than Meloni".

Moual is cautious. Today it belongs to Meloni,' she says, simply because Meloni is the prime minister. But what won the election, says Moual, was fear, and the desire to deny the existence of a generation that is 'essentially Italian'.

It is a vision, he says, that is "divorced from reality - and reality is Ghali's".

For those who live this reality, rap music remains one of the few ways to share their version of the world.

In this way, a new wave of rappers - to whom Ghali has paved the way and some of whom have signed with his Sto Records label - are confronting, often angrily, an Italy that cannot reconcile itself with the demographic future that awaits it.

In the summer of 2021, the number of sea crossings began to rise again.

In November of that year, Ghali's rap scenario became reality: he and Salvini were both at the San Siro stadium cheering on AC Milan, sitting next to each other.

After one of the team's black players scored, Salvini celebrated. In a video that has gone viral, Ghali can be seen swearing at Salvini as his friends try to restrain him. He shouts at him: 'Buffoon, what the fuck are you cheering for? A nigger scored. A nigger like me, like so many and like so many of those you let die at sea! Shame on you!

Soon after, Ghali began discussing with Mediterranea how he could support their mission beyond the small donations he had already made.

On 19 July 2022, Ghali announced on Instagram: "I bought myself a boat".

The photo carousel of the post includes a video clip of 'Mama' and excerpts of songs from his career in which he referred to or narrated crossings, the last from 'Bayna'.

Coincidentally, the Italian government fell the next day and a general election was called for September. Meloni focused her campaign on immigration, which she had previously equated with ethnic replacement, and promised a naval blockade.

On election day, Ghali voted at her old school in Baggio, posting photos of her ballot paper and Italian passport on Instagram with this message: "Distrust of Italian politics and the right to vote are two different things. The right to vote is one of the most important forms of individual freedom we have, and there are those before us who have fought for it all their lives. Don't be lazy and don't make excuses.

Meloni won with 26% of the vote and formed a coalition government with the party led by Salvini and that of former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi (who died in June 2023).

With the arrival of the new year, the new Prime Minister continued to focus on the crossings, issuing Decree 1/2023, which aims to minimise the time spent at sea by rescue vessels. At the end of January, she signed an $8 billion gas deal with Libya that includes the delivery of five more patrol boats to stop attempted crossings.

Ghali commented on Instagram: "It is absurd to think that part of the taxes we pay as Italian citizens will be given to the Libyan coastguard to imprison, torture, enslave and deprive of all human rights thousands and thousands of refugees in Libyan concentration camps. ... [They say they don't know what will happen in Libya if we push these people back. All lies, they always knew everything.

Meloni also wanted to reach a similar agreement with Tunisia. The space for such an agreement opened up because the Tunisian president, Kais Saied, who had sacked the prime minister in 2021 and then dissolved the parliament, was now in a position to act more autonomously.

Then, on 21 February, Saied gave a speech in which he outlined his version of the racial replacement theory: that there was a conspiracy to replace Tunisians with black sub-Saharan migrants, described as 'hordes' bringing crime.

The violence unleashed by his speech triggered a wave of panic-driven departures. Business has soared for traffickers.

I am as ashamed of him as I am of Salvini,' says Ghali.

Despite the cold winter sea, a smugglers' boat set sail from Turkey on 22 February. Each of the at least 185 people on board - mostly Afghans, but also Iranians, Syrians, Pakistanis and Iraqis - paid around 8,000 euros for the passage. (A one-way flight from Istanbul to Rome would have cost around 200 euros).

Meloni's new laws against search-and-rescue vessels came into force the next day, and the Italian authorities seized the MSF ship.

The Mare Jonio, with Bayna on board, is still trapped in the port of Trapani.

On the night of 25 February, Frontex, the EU border agency, alerted Italy that the boat was heading from Turkey towards the Calabrian coast.

But before dawn, with the beach in sight, it broke in two.

Fishermen see the passengers signalling with the lights of their mobile phones and rush to help. They found lifeless bodies lying on the sand.

This is the beach of Steccato di Cutro, a modest village of 450 inhabitants in the low season. Its streets bear the names of distant cities and countries - via Oslo and via Zurich, via Athens, Dublin, Prague, Barcelona, Tbilisi, Tirana, Niger, Ethiopia - as if to attract tourists from all over the world. Instead, the world's problems were thrown onto the shore.

The tragedy sparked an outpouring of grief.

In nearby Crotone, the town of 60,000 where survivors and the dead were relocated, Italians paid their respects to the bodies by parading through a gymnasium where the coffins were laid out, leaving offerings of stuffed animals for the coffins containing babies and young children. Family members who had travelled from other European countries bent over the coffins.

Feelings of anguish mixed with anger ran high as news emerged that the Italian authorities had known of the boat's imminent arrival and had sent the Guardia di Finanza instead of the Coast Guard, treating the ship as a police operation rather than a rescue. Due to rough seas, the Finanza returned to port and Italy made no further intervention.

Instead of saving lives, local, regional and national authorities mobilised by sea, air and land in the much larger and costly operation of recovering the bodies still missing. Tents were erected on the beach near a memorial made from the wreckage to hold the bodies, and helicopters hovered above the waves in the search.

Almost a month after the shipwreck, the mayor of Crotone, Vincenzo Voce, spoke of the people involved in the operation to recover the bodies: 'Everyone is asking for psychological support'. He added: 'It is not easy to go and recover the remains of a body that has been in the water for days.

When the question of what to do with these remains arose, the mayor and council of the tiny town of Marcellinara realised that although families wanted to bury their loved ones in Calabria, there were no Muslim cemeteries.

They set aside part of the municipal cemetery for Muslim burials. The mayor, Vittorio Scerbo, called it 'a small gesture'. Repeating what has become a motto among Marcellinara's authorities, he said: 'We did it for the dead, we can also do it for the living.

Meloni blamed the boatmen for the loss of life.

She promised to put an end to such tragedies by stopping the departures, saying she would do so by 'demanding maximum cooperation from the countries of departure and origin'. In April, she signed a border control agreement with Tunisia.

His government also signed an emergency decree that includes measures to increase penalties for smugglers and traffickers, reduce integration programmes, and create more detention facilities and new detention centres for migrants awaiting the outcome of their asylum applications (which can take up to two years). The decree became law in May.

Ghali's trip to Trapani in the wake of Cutro has raised interest in Mediterranea, but the Mare Jonio is still waiting to return to the rescue.

For Laura Marmorale, president of Mediterranea, Ghali's activism is remarkable. Not many public figures have come out in defence of civil rescue operations, tackling difficult and divisive issues such as immigration or maritime rescue,' she says. When someone does, they become the target of online hate and abuse, and are attacked in articles in the right-wing press. Taking a stand also means putting your career on the line.

Ghali acknowledges the disproportionately hostile reactions, but says he accepts them as inevitable. What disappoints him, he says, is that he has not found support for his support for Mediterranea among what he calls influential Italians. When he donated Bayna, he also launched a crowdfunding campaign to buy a second boat. Those who donated generously and amplified his message on social media, he says, were 'just people like me, children of immigrants. That is the most worrying thing. What I wonder is: do you have to live it on your skin to realise it?

As summer approached, the crossings, rescues and drownings resumed; in June, the migrant boat Adriana capsized and sank off the coast of Greece, killing more than 600 of the 750 or so people on board.

And so the usual debates and recriminations and essentially inadequate solutions returned. In mid-July, Meloni, Ursula von der Leyen, the head of the European Commission, and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte travelled to Tunisia to announce another agreement with Saied, in which the EU will essentially pay Tunisia to prevent migrants from taking to the sea, while several dossiers document the Tunisian authorities' abuse of black migrants.

The Mare Jonio has not yet returned to sea.

Ghali, who recently turned 30, says he used 2023 to recalibrate himself. In 'Pare' he sings: 'Sometimes you have to be born again to leave things behind, which I then destroy so that they don't destroy me'. He deepens his knowledge of Islam and during Ramadan goes to Saudi Arabia for the first time to perform Umrah with his mother; he includes Mediterranea in his prayers.

But he is quick to point out that he has always believed in God. The difference is that, after years of having to "suppress my origins, my traditions, my beliefs in order to fit into a society that does not accept you for who you are", he is now making them much more public. He wishes there had been a famous Italian who had done the same when he was a child: 'Some days would have been much better'.

In July, he travelled to Tunisia for the first time since the outbreak.

In the early hours of the morning before he left, still awake after performing at another rapper's concert in Milan, he scrolled through long-ignored messages on Instagram. He was stunned by all the messages he had received from Tunisians over the past few months, asking for help to finance the crossing.

In a surreal twist, among the messages was one from the young man who played the protagonist in the 'Mama' video.

Speaking from a Tunisian café overlooking the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean, Ghali said: 'Despite all the bad news that comes, despite how dangerous it is, more and more people are crossing the sea and asking me to help them.

Ghali says the argument he keeps hearing - that North Africans have no legitimate reason to leave because they are not fleeing war - makes no sense.

In Tunisia, you learn early on that you cannot dream,' he said. You are immediately disillusioned with the possibility of dreaming. What does a person do here, a person who resigns himself to no longer having dreams, who even stops dreaming? If you can dream in Italy, then Tunisians who want to do something in life will at least leave to be able to do it, to have the right to dream'.